School’s history lesson

Date published: 22 May 2009

Archive uncovers the story behind 175 years of the Blue Coat School

FOR 175 years the silhouette of the Blue Coat School has dominated the Oldham Edge skyline.

And now Oldham people will be able to learn much more about the building, the school’s traditions, history and the contribution its scholars have made to life home and abroad.

For the first time the archives of the school are being made available to the general public at an exhibition at Oldham Local Studies and Archives centre in Union Street.

Archive officer Jo Robson, who has been cataloguing the 2,700 papers, photographs, log books and other memorabilia since January, 2008, has put together the fascinating exhibition.

The Blue Coat archive is the first collection to go on to the electronic database which can be accessed by staff, and shortly by the public.

And people are being asked to record their own recollections of life at Blue Coat, or memories of family members who were former pupils, to add to the archive.

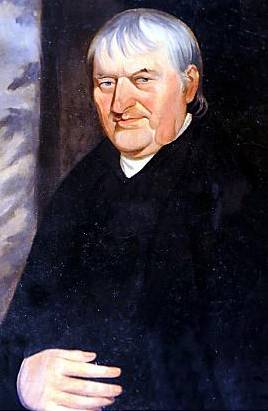

Blue Coat, in Egerton Street, was the brainchild of local philanthropist and businessman Thomas Henshaw, a hatter, who left £40,000 (worth £2.2 million in today’s terms) in his will for the endowment of the Blue Coat School.

But as the exhibition reveals, it was touch and go whether the school was built. Thomas added several codicils to his will, and was found dead in a reservoir at his works in 1810. An inquest found it was drowning as a result of insanity.

The will was challenged by his widow and niece in various courts, and it wasn’t until 1818 that his bequests were ruled valid.

The will did not include the cost of land or the building itself and, following a public meeting in 1825, a public appeal for funds was launched and offers of land were received.

The Blue Coat foundation stone was finally laid in 1829 and the school — designed by architect Richard Lane, who also designed Oldham Parish Church — opened in 1834.

It initially took in 48 boys, from nine to 11, who had to pass a test on the New Testament, Apostles’ Creed, Lord’s Prayer and Ten Commandments.

Between 100 and 130 boys boarded therel, with a strict uniform and school routine, until 1952.

When it opened, the bugle sounded at 6am and the top pupils took what they learnedt from teachers and disseminated it to the younger boys by the monitoring system.

They were responsible for a group of boys, not just teaching them, but organising slates and chalk to write with.

Jo Robson believes that pupils from both 19th and 20th centuries would recognise each others’ general lifestyle: “It would be very much the same. Boys did chores, chopped wood, peeled potatoes and did a percentage of the cleaning.

“It left them with a very rounded, disciplined ethos, and not just in the classroom, in boarding life as well.

“Many said it prepared them to join the Army, and made them well disciplined and self sufficient.”

The aim was to get the boys apprenticed to a trade to set them up for a productive, working life.

Many went far beyond that — as the exhibition reveals many went around the world.

Oswald Chorlton left in 1875 and was apprenticed to a grocer. But when his mother died from TB he was encouraged to go abroad to “purge” himself of the disease.

He went to Canada only to have to travel again to escape small pox. He returned to England in 1897, then travelled to Australia where he worked as a grocer and joined the local militia. Finally he settled back in England in 1905, at a grocer’s shop in Leyland , Lancashire.

John Raw Howard left school in 1842 and went to the China Sea as an apprentice sailor, before working on the railways and as a colliery manager in Wakefield, Yorkshire.

He then went to Labuan, a Malaysian island, where he became the surveyor general of the colony and superintendent of conscripts in 1868.

He died after challenging a blockade by three Spanish warships on a neighbouring island, leaping from his ship only to die of exposure.

In 1944 the Education Act made universal education freely available to children up to 15, and Blue Coat admitted its first girls when it became a mixed secondary modern in 1952, taking pupils from surrounding parish schools.

The exhibition runs until the end of October.

Want to know more?

A talk on the exhibition will be held on June 10 at Oldham Local Studies and Archive.

The 6pm talk by archivist Jo Robson will look in detail at the collection, including how it can be used by researchers. Archive viewing is from 5.30pm.