The day war broke out

Reporter: Janice Barker

Date published: 03 September 2009

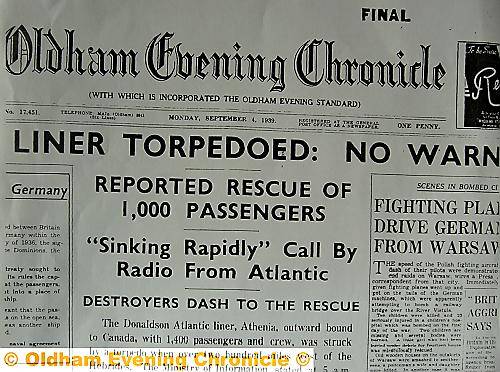

The momentous news that greeted Oldhamers returning from their Wakes holidays

Seventy years ago today, the Second World War began for Oldhamers with a radio announcement from London.

The momentous news from Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain that “this country is at war with Germany” was heard on radios across the town.

The day war broke out, life in Oldham carried on as normal: schools were still open and people went off to work.

It was the end of Oldham Wakes and the Wakes fair — people returned from happy holidays to a country at war.

But some things were already abnormal — a blackout was already enforced, children evacuated from Bradford arrived in Saddleworth, the WRVS was appealing for blankets, and air raid sirens were tested.

Fred Baxter, former Oldham hospital administrator, magistrate, Mayor and councillor, was a 14-year-old at Oldham Municipal High School in Greengate Street, and remembered it caused an extended summer holiday for him.

“We were told not to go back until they had dug air raid shelters in the grounds,” he recalled.

Living in Whetstone Hill, Derker, he recalled looking down on the bombing of the Belgian Mill in Blackshaw Lane, Royton, a year later, when incendiary bombs were also dropped on Derker.

He added: “I looked forward to being called up. I was in a reconnaissance corps with a Cavalry regiment which used tanks, not horses.”

The war took him to Ireland, France and Germany. And another former Mayor, now Honorary Alderman Jack Armitage, who was 15, was a “flour lad” with the Co-operative Society, weighing out packets for customers in 1939.

He said: “I remember there was suddenly an air of solemnity after we heard Mr Chamberlain’s very serious voice on the radio.

“But as a young lad I was thrilled to bits, and my big fear was that war would be over before I would be 18 and able to go. I wanted to go in the Royal Horse Artillery — it just shows how thick you are at that age, it never crossed my mind that we might lose.”

At the time he was living in Granite Street, Derker, and remembers: “Five young men who lived near by went to war, but only three came back.”

After Chamberlain’s announcement of war, the BBC told listeners to expect air raid siren tests, but Mr Armitage now 84, recalled: “We had an air raid shelter near us, my uncle was in charge of it, and at first when the sirens sounded we went in the shelter, but we soon stopped that.”

After reaching 18 he would spend five years in the Grenadier Guards, going to Normandy and the Baltic, then two years with the Army of Occupation in Germany.

The territorial 41st and 47th Tank Regiments, which trained on Oldham Edge, were mobilised, and saw their first action at El Alamein, the pivotal north African battle. The 47th was shattered and tanks distributed across other regiments, the 41st went on to Normandy and after the war the bravery of its local lads was rewarded with the Freedom of the Borough.

On September 3, 1939, Oldham did not know the town faced six years of bombing, deprivation, rationing, a major contribution to the war effort, the joy of VE day, the desperate wait for the war in the Far East to end, ecstatic home comings, and mourning for those who failed to return.

Platt’s and Ferranti’s turned production to munitions, and as young men went to war women took their places on buses, trams, in council offices, and in factories.

In Chadderton, 18,000 workers built Lancaster bombers at Avro’s factory in Greengate, which took the war to German towns and cities.

Families in Abbeyhills paid the price of retaliation when a German V1 flying bomb killed 27 people on Christmas Eve, 1944.

And 27 also died in 1941 when 25 bombs dropped on Oldham in a random raid hitting Copster Hill, Breeze Hill, Oldham, Coppice, Hollins, and Hollinwood.

But perhaps Hartley Bateson, the great Oldham historian, sums up the spirit which helped local people get through the war.

After the 1941 raid, he recalled how, the following morning, a board nailed over a blasted window frame of a battered house displayed a notice written crudely in chalk: “He left the oven, so the dinner’s OK.”

Most Viewed News Stories

- 1You can score free tickets to a Latics game while supporting Dr Kershaw’s Hospice

- 2Primary school in Uppermill considers introducing new ‘faith-based’ entry criteria to tackle...

- 3Tributes paid following death of hugely respected Oldham community figure Dale Harris

- 4Public inquiry announced into rail upgrade that could leave villages ‘cut off’ for months

- 5Trio arrested, drugs and weapons seized following Chadderton raid